The Perils of Letting Coding Agents Write All of Your Tests by Ed Lyons

Test Facility, by Ed Lyons via Midjourney

The answer to potential mistakes by coding agents is often increasing the amount of test code. The theory is that if you write enough tests, the agent will see that some code it wrote fails them, and then it will repair the problems all by itself. Many organizations are making a big push to increase testing code to enable greater agent use.

Yet my experience using agents to write code and test cases has revealed that this formula does not work as well as imagined. Human decisions around test code that were made before we used agents were doing more good work than I realized, and they need to be restored.

Yes, creating more tests to protect against agent errors is a good idea. But this theory is undermined by an irresistible temptation: just how good those agents are at writing the tests themselves.

Perhaps if we humans wrote all of the test code manually, it would be quite good at constraining the agents. But that is not what is happening due to the new economics of coding with AI.

When developers learn to use agents to write software, they quickly discover that agents are incredible at rapidly writing a variety of tests. As most developers are not experts in the complexities of test writing, it is a relief that the agent knows so many patterns. After all, when is the last time you wrote complex mocking of components?

In addition, agent test writing is quickly embraced by developers who are hesitant to using AI, as it is an automation that does not feel like a threat to their core application development skills.

In this new agent-testing world, when you finish your ticket, you can remember, “Oh yeah, I need tests,” and then you ask the agent to do it. Voila! - you have instantly done the responsible thing. You submit your PR, and proudly mention that you created tests and they all pass.

And if you are assigned a task to add more tests, it is irresistible to subcontract this drudgery out to your agent, because, unlike you, it is very enthusiastic about doing the work. (Enthusiasm from coding agents is their most underrated power in a world of developers who often lack it for necessary work.)

As the number of generated tests grows and code coverage increases, it then seems reasonable for someone to crank out far more tests to cover all remaining code — a level that few team leads tried to achieve before AI. So someone tasks an agent with many hours of work to get the coverage to 100%. The outcome of this is a 15,000 line PR that gets coverage to 95%, impressing everyone, though not inspiring anyone in particular to review all of those tests.

But what… exactly… has been achieved ? Is the code safer from bugs? How many of the tests match real-world usage of your application? Has anyone really reviewed all these cases against requirements? The frequent temptation to accept generated application code without enough review is even stronger for testing code, which is rarely taken as seriously by application developers. This leaves huge amounts of test code unseen.

The software developers who scoff at non-programmers generating applications, yet generate hundreds of tests they don’t understand — need to be asked, “Who is the one vibecoding now?”

Because protecting generated code you don’t fully understand with other code you don’t understand at all is less of a shield than you think.

There are other risks around test code that were always there, but are made worse by casual use of powerful coding agents. For example, not all code should be tested in the same way. Complex components should not be part of unit testing, as they frequently require sophisticated mocking code to simulate other parts of the system. Human developers have at times become too ambitious with what unit testing can do, but are soon frustrated by growing configuration difficulties. They usually abandon the effort.

But speedy and optimistic agents are always up for the task, and can be directed to put enormous resources into testing complex components in unwise ways, especially when you are generating code for components of varying complexity all at once. These tests can end up being brittle, especially due to things like asynchronous function calls, which cause instability in test results.

Having generated a large number of tests myself, I did some experiments to try to get the agent to fight the complexity and entropy I created. I asked it to use more durable patterns, and wrote instruction files that constrained what it could do.

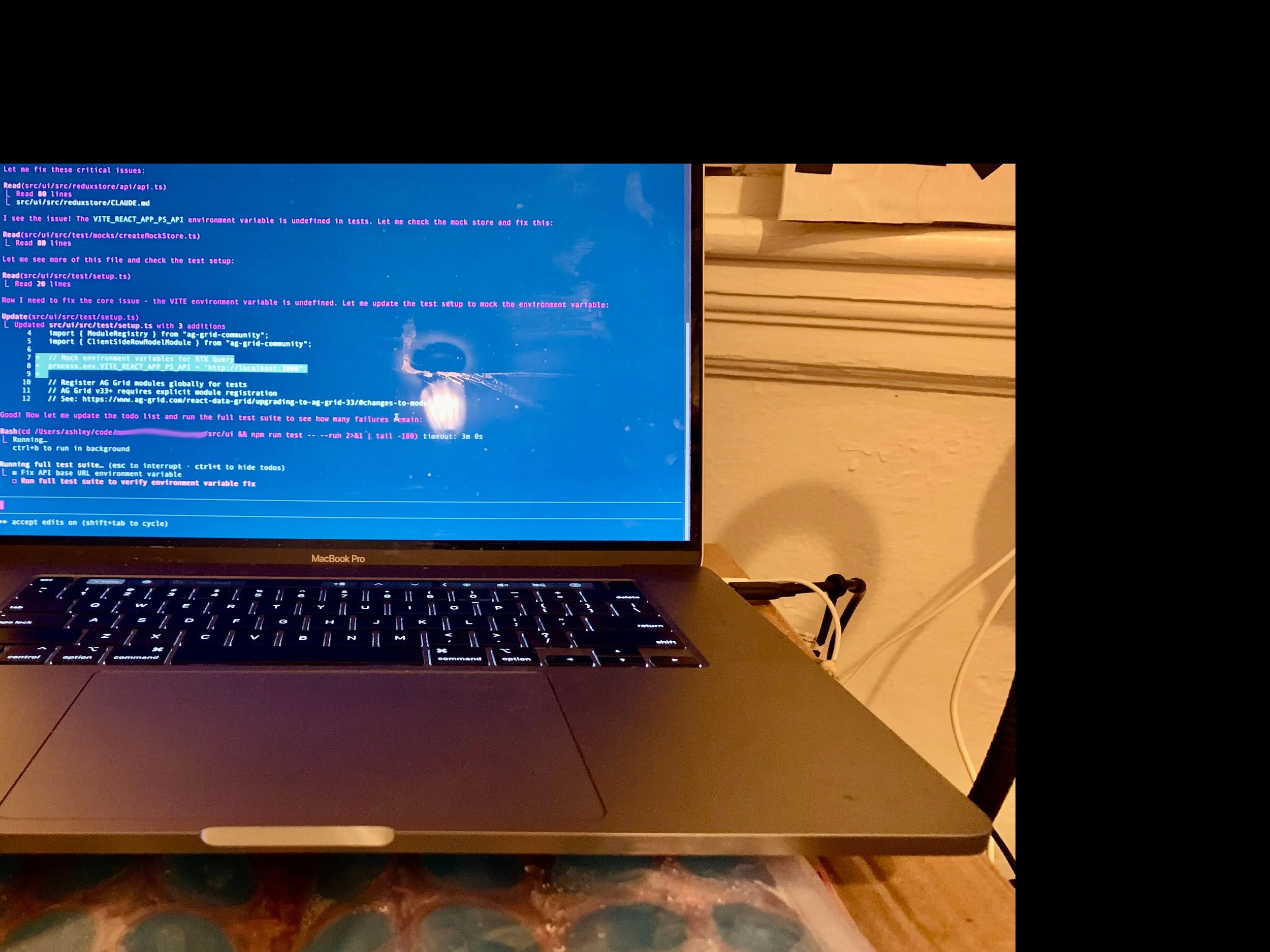

I did so much refactoring and retesting, I blew through my weekly token budget in two days. Hours of work maxing out my CPU and RAM got my laptop so hot that I put a rectangular ice pack under it while I was working.

A big strain on my machine was that the agent would kick off sub-processes to run various tests, analyze the failures, and come up with solutions, often at the same time. This would normally be quite efficient, but all the changes seemed to confuse the agent, which kept running more tests and doing more thinking.

What made things even worse were my application code requirements to solve minor coding style and typing errors while it was in the process of changing code. That meant fixing a compiler warning would cause something else to break that would cause re-testing of a component while other test fixes were in progress. Churning for hours around so many changes in a large test suite is why my laptop almost melted.

All of the threads and text outputs also left me so engrossed in the agent window that I wasn’t paying attention to the code anymore. After two days of noticing that endless refactoring of several complex components wasn’t going anywhere, I decided to actually look in the directories and noticed that there were duplicate copies of the same test in some places. This was due to an earlier request where I asked the agent to move tests into new directories, but it didn’t delete all of the old copies. So the agent was seeing one test cause errors, and was frustrated that making changes to the other copy weren’t stopping the failures. Amid thousands of lines of output crossing my screen, I didn’t notice the path differences that showed the old copies were still there.

Once I killed all of the sub-processes and got rid of the old copies, I looked at the mocking code and asynchronous helper functions. My setup code had gotten very complicated through all of the refactoring and fixes, and I no longer understood what it was doing.

I repaired all of the tests by hand, made peace with the mocking code, and I came to some conclusions about how to write and manage tests going forward.

Talk to the agent about testing before generating code

Proper design of test code was always important, but if we are going to generate far more of it, we need to go through the same exercises that work with application code: we need to talk to the agent about requirements, and then vet choices and plans before having it write any code. We should be asking it what kinds of tests are most appropriate for certain components, and then collaborating with it to come up with the right approaches.

Just as I had to once learn that simply asking an agent to generate an application feature was far less effective than asking for a plan, I had to learn that telling it, “Now go and write tests for….” is only going to work well for straightforward utility functions.

Be on the lookout for an agent changing application code to match a failing test

I do not think this happened to me, but I have heard stories about this from friends. To guard against this, before I do test code work, I check in all application code so that any new file changes to application code will stick out as having been modified.

Create a process for reviewing the intent of test cases

I know that I should review all of the test code, but I want to focus on the difficult pieces, such as complex business logic, asynchronous functions, and mocking utilities. For the cases themselves, I have found it very helpful to ask the agent to create little markdown files in each directory that explain in plain English what conditions were tested, and what the expected values were. Reading these files is far easier for following test scenarios than reading the code itself, which has a lot of distracting implementation details. I can then highlight tests that do not provide value and say, “Please remove these.”

Come up with the way your agent will write, fix, and refactor testing code

I also learned that it mattered a lot how an agent ran tests, when it ran lint and type checking, and other process details. A lot of problems I experienced were due to my agent getting confused by kicking off too many processes that affected each other - never mind how many tokens were squandered through all of this unnecessary processing.

As an example, I finally got control of one-out-of control debugging session by writing, “Please fix the broken tests in this way: run the entire suite once, and write the results to a markdown file. Then do an analysis of potential fixes and update that file. Then, proceed to fix tests, one at a time, running that test only. Do not run linting or type checking until all tests are finished. Only run the entire suite when all changes are fixed to verify they all pass. Please fix the easier tests first and then ask me to confirm before continuing. Do not kick off background processes while fixing the tests.”

That new process got my laptop fan to turn off. I could use the markdown documents to re-start work in a new session after my maximum conversation length had been reached, which happened often.

Create testing specific instructions and sub-agents

Existing agent instructions for your overall application are useful, but I learned that specific instructions around testing, especially giving code examples of patterns I wanted, helped the agent. I also created a sub-agent in Claude that was dedicated to testing only, and that made fixes more efficient. When I learned that a pattern was not reliable in our build pipeline, I added an instruction advising against it in favor of a new one that worked well.

In conclusion, the big takeaway for me after working with a lot of generated test code is that it needs to be taken as seriously as application code. I needed to slow down the agent, discuss plans, review results, and only let it run when it had been properly instructed and restrained.